Would you play a game you keep losing at?

It was the end of our second match of War Chest and my girlfriend and I were savouring how much fun we had with the strategy board game.

Then she said, “I really like this game. I don’t wanna keep losing, though.” There was no bitterness in what she said. Just a slight longing. And we continued discussing the different strategies we used in the chess-like game.

I remembered feeling the same way as her when I introduced Hero Realms to a friend who ended up beating me almost all the time. I wished I’d won more but this feeling was second in importance to my general satisfaction at the tactical play of the deck-building game.

Why focus on the low point of a game, the losing bit? Because I think it offers one of the truest, and perhaps overlooked, barometers of how good a game is: the experience of playing it can be so much of a joy in itself that victory doesn’t have to be the end-point.

The game within the game

That is, if you see that there is more than one winning experience in every game. There is the explicit goal that is laid out as the game objective: beating your opponent, getting the most points, solving a puzzle, catching the murderer, etc.

And then there is the unstated goal of inhabiting a game, where you learn and familiarise yourself with the range of outcomes a game can have. This is like unlocking embedded experiences from a game’s rules and lore.

Let’s dive deeper into War Chest to tease out these two goals. In the game, you play as battlefield commanders competing to gain control of locations on a battlefield. In a two-player game, the number of locations each of you have to gain control of is 6. That’s by and large the explicit goal of the game.

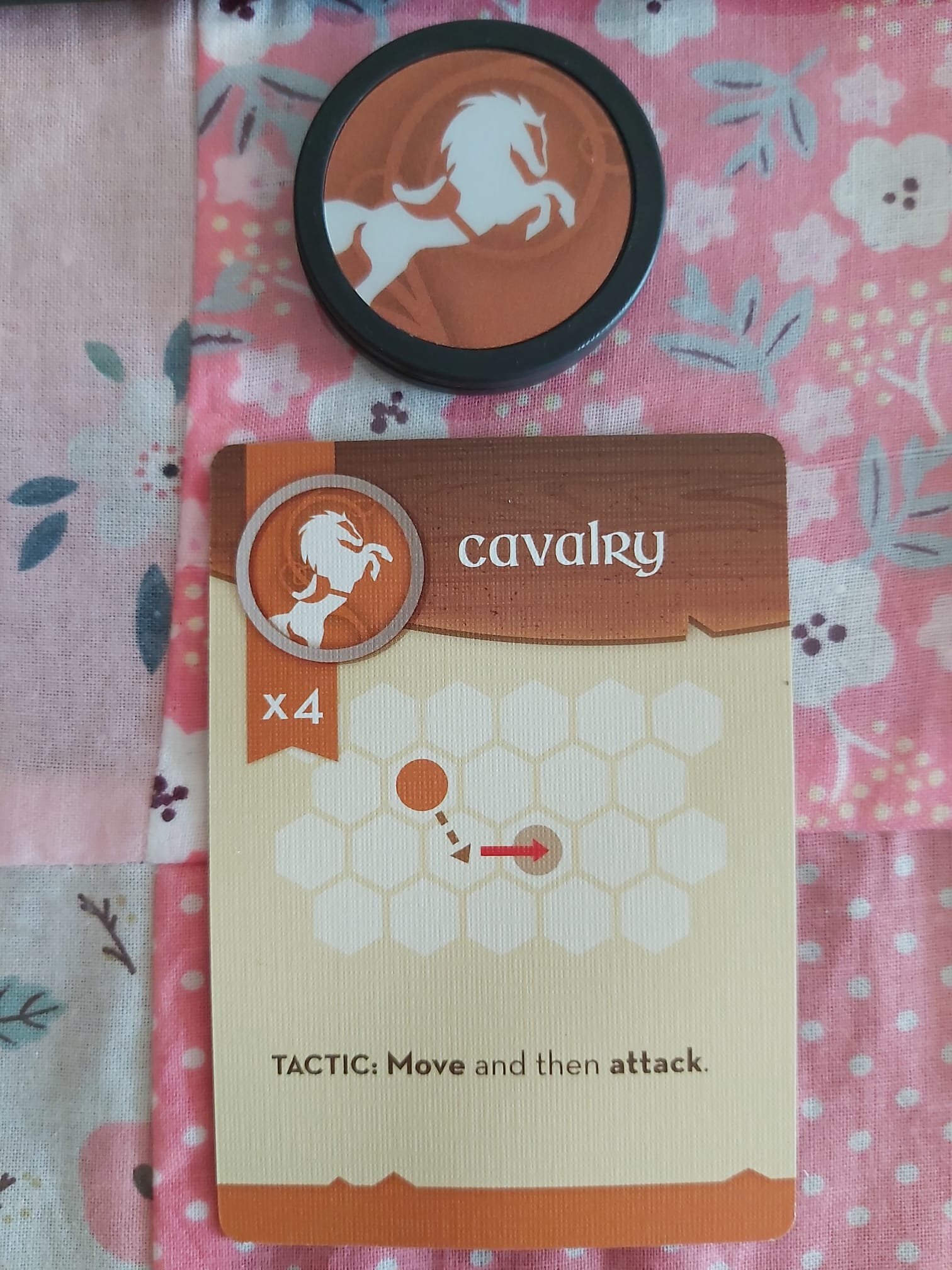

To gain control of a location, you will have to deploy and move different army units. Each unit is represented by a coin and has a unique tactic (or ability). The Cavalry, for instance, can move and attack simultaneously, while other units can usually do only one at a time. The Archer can attack a unit two spaces away, instead of having to move to the space adjacent to a target for an attack as is the case for most other units.

In trying out different tactical movements, you start to think of how you can pair different units effectively. Essentially, you get a sense of the breadth of game experiences provided by War Chest. In other words, you start achieving that second goal of inhabiting a game.

Admittedly, how much this second goal feels like a victory depends on the replayability of the game. The more variations in play a game allows, the more you want to explore it and be better at it.

One of the perks of inhabiting a game is being able to discuss it with others who have also inhabited it. On a forum like Board Game Geek, you can find posts on strategies for War Chest and share your own. This can immerse you further in the game and add more fun to your playing experience.

Now, I’m not suggesting that winning, in the most explicit sense of beating your opponent, is irrelevant. After all, without this goal in mind, you wouldn’t be motivated to explore the different strategies and experiences of a game in the first place. And if you’re not committed to beating your opponent, you’re not playing in the spirit of the game and may end up ruining the fun for everyone.

Rather, I’m simply saying that a good game can be a great companion, whether you tend to win or lose at it. You simply have to engage with it on its terms and take up the challenges it throws your way.

If there is a range of experiences for you to explore and enjoy, there’s always a reason to come back for more. And, as a bonus, you will never have a reason to be a sore loser.